In its citation for the World Cinema Documentary Special Jury Award for Craft to Nocturnes, the jury at the Sundance Film Festival stated: “The images and sound in this film immediately invoke in the audience a meditative state as they enter the film’s world, at the same time bringing a laser focus to the film’s main subject. The confidence of the cinematography and sound design in building this story is part of its power and allure”.

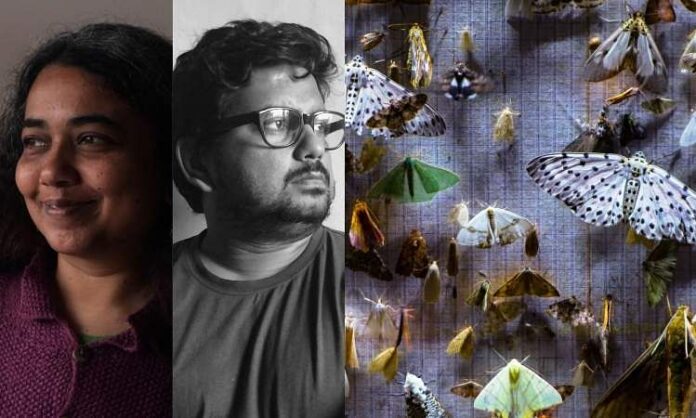

Nocturnes is indeed immersive, experiential cinema at its most hypnotic. Breathtaking, vivid visuals (DOP Satya Rai Nagpaul) and stunning sound design plant the viewer right in the middle of the universe of moths in this rare Indian entomological documentary. Filmmakers Anirban Dutta and Anupama Srinivasan follow ecologist Mansi Mungee and her assistant Bicki in their quest into the dense forests of Arunachal Pradesh in Northeast India to shine a light on the secret lives of moths. The intimate peep into the world of insects is juxtaposed against the overwhelming expanse of nature.

There is the tireless, laborious work and extraordinary commitment of the researchers—the grind of putting up the huge screens, illuminating them to draw the moths, staying up nights, becoming nishachar (nocturnal) like the insects themselves, battling inclement weather, spending long stretches of time alone, away from home and family, and then the nitty gritty of measuring the moths, examining and recording them for shapes and sizes, forms and colours. The film acknowledges science and the scientists but eventually makes them a conduit for the viewer to experience the many mysteries of nature and value and appreciate it for the gift that it is for humanity.

Nocturnes also plays with the idea of temporality and permanence. It captures small triumphant moments, long waits and idle pauses in the scientific pursuit as well as the microcosm at large to give a feel of the span of time in that space.

In a conversation with Cinema Express after the film’s premiere at Sundance, Dutta and Srinivasan dwelt on what went into its making. Excerpts:

Nocturnes is about a unique subject—the inner lives of moths. What took you to it?

Anirban: We have lived for a long time in Delhi. The sheer noise level that we experience there is cacophonic. There is a constant hum even when you listen to music at home. We’ve both felt that there is something very basic that has been taken away from us. We were thinking of making a film which would help us reconnect with nature and to some simple sounds like that of the water droplets or of the wind. We were missing that “thehraav” (repose) because we were always running around in Delhi. We had a chance encounter with Mansi [Mungee] in Uttarkashi, when we were doing another project also on nature, on the snow leopard habitat of Uttarakhand. She told us about this incredible landscape, how she puts up these moth screens and thousands of moths slowly come down on it.

I have been working in the Northeast from 2005, and Anu [Anupama Srinivasan] and I have also made another film in Manipur, in the Naga Hills, called Flickering Lights. The Northeast is our favourite place. So, when Mansi said, it is in Arunachal Pradesh, in West Kameng district, we decided to check it out. When we went there, we were blown. I grew up in Andaman and Nicobar where we used to have these outdoor cinemas. They’d bring film reels and project them on makeshift screens. We would run out of our homes to watch them, like those moths getting attracted to the lights. The moth work brought back all those memories.

It’s a subject we don’t associate Indian documentaries with…

Anupama: There has been a tendency to feel that film festivals, especially in the West, will accept Indian documentaries only if they are about a very serious social issue, or about trauma or like a hero story, with somebody fighting against all odds in the corrupt system. The expectations of films from South Asia are of a certain kind. This was also at the back of our minds—why should we, as filmmakers, as intellectuals, artistic people living in today’s world, feel ghettoized and feel compelled only to talk about certain issues and only in certain forms? So, in this film we haven’t followed any template, plot point kind of thing at all. It’s just our expression. This film allowed that possibility of cinematic expression. The story is very basic and simple, and the whole film, in a way, is a cinematic expansion of that. So, we could really get into the sound and the visual exploration in a very wonderful and detailed way.

How much did you have to travel, and how long did it take you to shoot the film?

Anirban: The moth work is seasonal. It doesn’t happen in winters, and it was very difficult for us to film during heavy rain. So, it was over a few trips between 2019 and 2023.

Anupama: But the primary, principal photography started end of 2021 because in the middle we lost a little bit of time to Covid. 2021, 2022 were our two main schedules. We followed them [Mansi, Bicki and team] wherever they went but it was all in a relatively small area of the Eaglenest Sanctuary, and the surrounding forests, in West Kameng district of Arunachal Pradesh. A lot of it is in the community forest and some of it is in the sanctuary.

Anirban: It’s called Singchung Bugun Community Reserve. It’s a special place in India where the community has lent its own land to create a buffer zone and a few years ago Ramana Athreya [birdwatcher and astronomer at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune], who is part of our film, discovered and described a bird species called the Bugun liocichla. It’s such a special jungle where new species are still being discovered. The biodiversity is mind blowing, the moth is only one small part of it. It also has a very special cat population. There can be several films made on just this forest.

Anupama: And I think only about 10 per cent of the species have been described till now, so there is that much scope for finding new things here. But it’s a challenging physical environment to work in. So, there are just a few scientists working here. A lot of people are quite daunted by just having to live like this and work in very difficult circumstances.

Anirban: As you saw in the film, it is so remote and so difficult to get to. But if you have the patience, or if you have the calmness, to wait for things to happen, then it can be rewarding, both for scientists as well as filmmakers

The film makes for an incredibly immersive experience. What went into its visual language and sound design?

Anirban: In 2019, we went to the forest with the kind of equipment we usually take for documentary shoots—shotgun, boom microphones, lapels, etc. When we came back and heard and saw the footage, we felt what we had been hearing there was not coming across in the footage. It felt like a big loss. At that point we started researching on how to record the sound. We had a wonderful sound recordist called Sukanta Majumdar, who teaches at SRFTI (Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute). When we went there next, we went with multiple microphones, a few mono microphones, we had microphones which we clipped onto the screen to get the ‘tuck tuck’ of the moths, the walking of the insects. We went with stereo microphones and added an immersive microphone, which was a 5.1 microphone and we had 360-degree microphones which recorded the soundscape. We did hours and hours of recording. For example, in the film, when you see a transition from day to twilight to night, it is the recording of how the soundscape changes. We wanted to be true to that, and not use any stock, what we call the library sound effects. So, the thunder that you hear, the raindrop that you hear, they’re all from that place. That is the way we felt [when there]. We also felt that this kind of sound motivates the gaze. You will see more if you hear more. and if you see more, then you will hear more. It’s both the things that happen together. This film is as much about sound as it is about images.

We could do the film in Atmos. For the premiere we requested Sundance for an Atmos theatre. And so, when the moths were flying on screen, the sound made people think the insects were around them. They came out looking dazed.

Other than Sukanta, we had a wonderful young sound recordist, Neetu Mohandas. Our postproduction team was very special. Shreyank Nanjappa who is a Bangalore-based sound engineer and designer and we also worked with Tom Paul in New York who is an amazing sound designer and engineer. We were also very blessed to have wonderful co-producing partners called Sandbox Films. They are based in New York, and they make films at the intersection of science and art. It’s a dream to have partners and collaborators who believe in your vision and trust you.

Anupama: We were fortunate that from the very beginning we had Satya [Rai Nagpaul] on board. Apart from being an amazing camera person, he is very interested in entomology and has worked with insects and on wildlife. He knows the subject. He’s very sensitive to the forest, and to living and filming there.

We didn’t want to make picture postcard kind of images at all, even though the forest is so beautiful. We wanted to find another way to capture that beauty. There are many shots of the fog just shifting and changing the way we look at something. The fog played a very important part because it gave a sort of dynamism to even very quiet looking shots.

I think a very crucial aspect was how to film the forest in a different way. One which is very meditative and deep and moving, and not flashy. We decided not to go for very shallow depth of focus in which we are isolating either the people or the moths, or any aspect of the landscape, too much from the surroundings, because the whole philosophy of the film was that we are all part of the same universe, whether it’s human beings or moths, or the tree. We wanted to communicate that through our lensing. And so, we see everything in focus and for that we needed to figure out how much light was needed to have enough depth of field. We had to do many tests to figure out these technicalities.

We did use the macro lens in some shots to get the details of the texture and the little feather and the antenna, which is such a big part of appreciating the moth.

The film is about moths but then there are also the humans who take us to the insect world…

Anupama: The idea was not to focus only on human drama or human story. We wanted to bring nature and moths at par with it. But, at the same, we didn’t want to diminish the human beings. They were the reason we came to know about this in the first place, and it is their work that we are following in the film. So, the scientific work becomes like the thread that allows us to be there and explore the forest and enjoy the world of the moths. Human beings become our guides.

We also decided, almost as soon as we started, after the first schedule, that we won’t do any interviews. We didn’t want to get into those kind of documentary tropes at all. We were thinking about how we can understand a little bit about the humans through the pieces of conversation that they have with each other, whether these are about science or about the work, weather or about their personal lives.

There’s nothing didactic in the film. We are also not giving too much information and keeping everything understated so that every crumb of information that we do offer is readily received by the audience rather than they being fatigued by too many words.

Anirban: Mansi is an incredible character, her dedication, perseverance are amazing. Her assistant in this process Bicki is a fantastic guy. There is this friendship and camaraderie that all of them share. There is no exploitation here or anybody looking down on the other. Class barriers have been broken by Mansi. They have the most equal relationship. There is incredible partnership between the scientists and community. It’s a tremendous model to follow.

Anupama: We decided that Mansi is not going to speak about being a woman scientist or anything. It was so empowering to see an image of a South Asian woman just doing her job as a scientist and not having to explain or to give a back story to her life. She’s just a woman in the field doing her job with absolute dedication and rigor. We need to see more images, not of South Asian women as victims. But just doing the job. It’s inspiring for young girls to see that.

What are the plans ahead for the film?

Anirban: Anupama and I dream of releasing the film in India. It’ll be such a joy if we can get children to come and see and experience this film. Forests are disappearing, environment and nature are being taken away from us. We want to bring the awareness of this reality to our children and young people.

#Anirban #Dutta #Anupama #SrinivasanNocturnesis #sound #images #Cinema #express